Networking basics

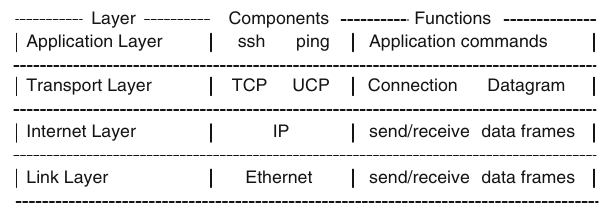

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol)/IP (Internet Protocol) is the backbone of the internet. There are 2 versions: IPv4 (32-bit addresses) and IPv6 (64-bit). The figure below shows the TCP/IP layers:

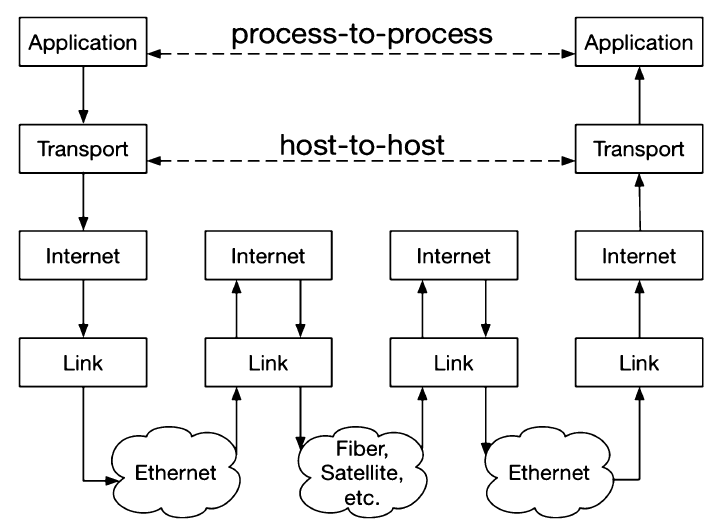

The top layer shows applications which use networking to transfer/collect data. They either use TCP or UDP (mentioned later). Data transfer at this level is only logical, the real transferring takes place at the bottom two layers (Internet and Link layers). This is where the data packets are divided into data frames for transmission over physical networks. This is represented in the data flow diagram below:

Every host (device supporting the TCP/IP protocol) is identified by a 32-bit address called an IP address. These are represented in a dot notation where the individual bytes are separated by dots. A hostname (i.e www.) and IP are the same, only the DNS (Domain Name System) translate between the two for simplicity. There are two parts to an IP address: NetworkID field and HostID field, where the leading two bits are the NetworkID and the rest the HostID. Data intended for an IP address are sent to a router with the same NetworkID, this router will then forward the packets to a specific host on the network with the same HostID. Every host has a localhost name (default IP: 127.0.0.1). IP protocol is used for sending/receiving data packets between IP hosts, operating in a best effort manner. This means there is no guarantee that packets will arrive at their destinations or arrive in order, thus IP is not a reliable protocol. Reliability, if needed, must then be implemented above the IP layer.

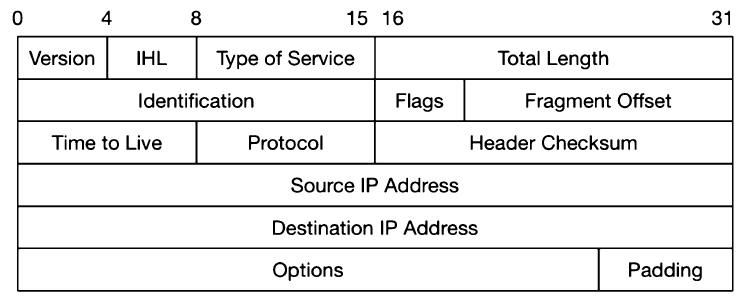

An IP packet consists of an IP header, sender and receiver IP addreses, an IP header looks like this:

It is usually not possible to send data packets directly from one host to another due to the distance between them. Routers are special IP hosts which receive and forward these packets, so if one receives a packet not meant for them, it will pass it on to the next router, which is called a hop. If however the packet does not arrive at its intended destination it doesn’t simply stay hopping around on the network. All packets have a Time-To-Live (TTL) count in the header, its job it to reduce by one upon each hop, and when it hits 0 that router will drop the packet. This number can be max 255 (8-bit).

The UDP (User Datgram Protocol) like IP, doesn’t guarantee reliability, but is fast and efficient. This protocol is used by applications where reliability isn’t essential (e.g ping). The TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) does guarantee reliable data transfers, but is much less efficient.

Each host may have multiple TCP/UDP connections happening at once, thus they all must be uniquely identified by a triple:

Application = (HostIP, Protocol, PortNumber)

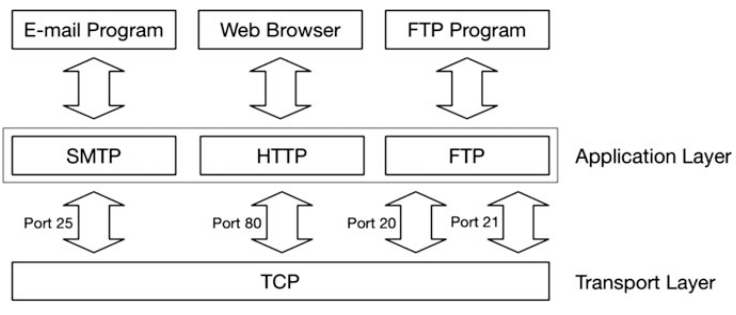

Where PortNumber is a unique unsigned short integer. In TCP applications the first 1024 ports are reserved:

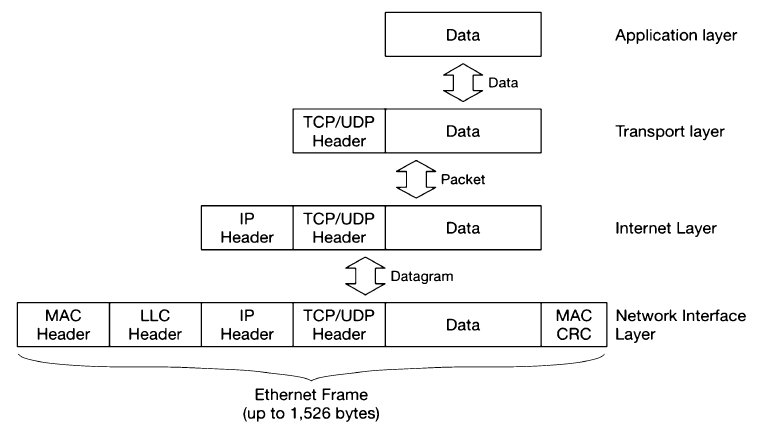

The dataflow in TCP/IP networks looks like this:

Where each layer adds some form of data as a header, and shows the direction these packets go through each one. The receiving host translates the data going in the opposite direction to this chart.