FUSE

FUSE (filesystem in user space) [1]

What is FUSE, and why use it?

FUSE is an open source framework which allows you to build filesystems in user space, compared to the conventional kernel space route. Building in user space is said by many to not be suitable for production, and also that the overhead is too substantial to be of use. But this allows the programmer to work in a ‘friendlier’ environment, gives a much larger toolset to work with and probably most importantly, it doesn’t crash the system on a bug like kernel programming does. It is important to note that if Unix FS were created in user space then they would be readily accessed under Windows.

FUSE architecture: how does it work?

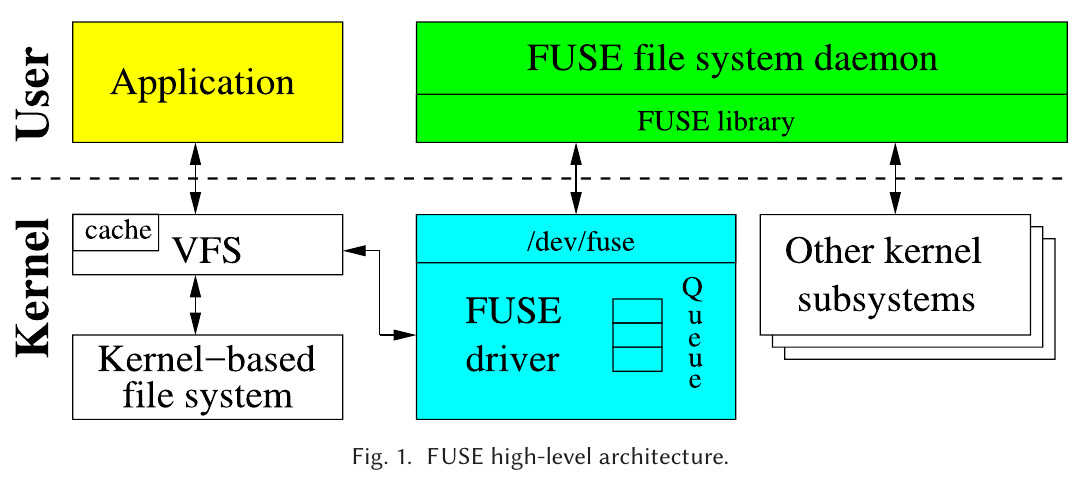

FUSE has a kernel part and a userland part. The kernel module (fuse.ko) and a fuse daemon, they communicate via a character device /dev/fuse. Upon initiation the fuse kernel module registers 3 filesystem types within the VFS: fuse, fuseblk and fusectl. The fuse type is for stackable (i.e on top of an already existing, kernel FS)/in-memory/network filesystems. fuseblk is for block devices containing user space file systems. fuse and fuseblk will be what is referred in this post as FUSE. Finally fusectl allows users to control and monitor FUSE FS behaviour.

Due to the FUSE filetype being able to represent many different FSs, unlike kernel-level FSs (e.g Ext4), they have a name attached to them when listed by Linux.

Side note: VFS [2]

The VFS (virtual file system) in Linux is used to give a level of abstraction to user-space applications about all the mounted filesystems, which allows for a unified look and feel. It does this by abstracting out the common filesystem code from each mounted filesystem to make a seperate layer, which in turn calls the underlying filesystem to manage its own data.

All POSTIX system calls (related to files/directories) must go through VFS first before reaching any underlying filesystem, this is the “high-level interface”. The “low-level interface” is the communication between the VFS and file system itself, called the VFS interface. Filesystem developers must supply the VFS with all the required VFS interface methods for that filesystem (read/write/readdir/etc). It is because of this interface that allows for all different filesystem types to coexist due to the VFS not needing to know where the file is located, only where to find the filesystem operations to work on the file.

When a filesystem registers with the VFS, it is simply providing that list of addresses containing the methods required. For example, a filesystem has just been mounted at /mnt and the user is requesting a read operation on one file (read("/mnt/foo/file.txt")):

- The VFS first searches for the FS (filesystem) requested in the /mnt directory

- It then finds that FS’ superblock and its root directory (/mnt/) from within the superblock

- The VFS can then find the foo/file.txt file path

- It then creates a v-node and makes a call to the containing FS to collect the information from file.txt’s inode

- This is then copied to the v-node (in RAM) along with other info which includes the pointer to the table of function calls to be used on v-nodes from the underlying FS

- Once the v-node is created the VFS adds an entry into the file descriptor table for the calling process and sets it to point to the new v-node, which is returned to the calling process, allowing it to now make read/write/close calls on the file

- Later when the caller makes a read call on the file using the fd, the VFS locates the corresponding v-node from the processes file descriptor table, follows the pointer to the table containing all of the methods of the underlying FS containing that file (which themselves are addresses located in the FS itself)

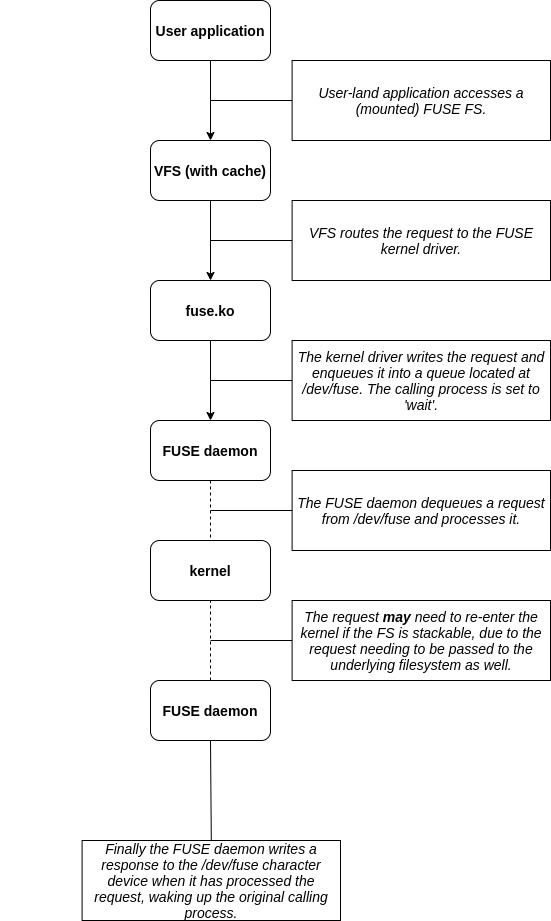

The image above shows a high level overview of the basic communication between FUSE and the VFS. In more detail, if a user-level application accesses the FUSE FS:

APIs: Low-level vs High-level

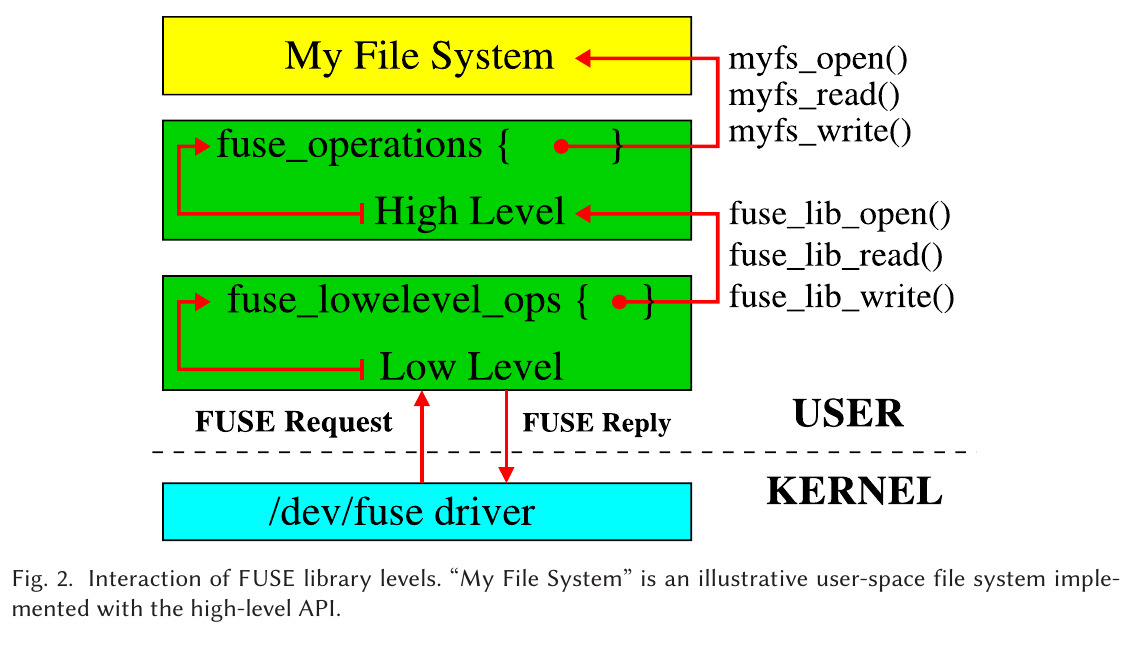

FUSE offers developers two different API levels to choose from: a high-level and a low-level. A high-level filesystem implementation would see a simpler codebase but generally worse performance compared to its counterpart. The low-level API is the only one of the two which communicates directly with the kernel, meaning it has 4 key differences:

- It receives and parses kernel requests

- It sends properly formatted replies to the kernel

- It facilitates filsystem config and mounting

- Finally it hides version differences between the user and kernel spaces

This means that the high-level API builds on top of the low-level, and all requests/replies must be passed through it if the high-level wishes to communicate with the kernel. One reason the complexity is reduced in the high-level is the fact that developers are not forced to do path-to-inode mapping, rather they are given the pathname directly. This is shown here:

Side note: inodes [3]

In modern Linux systems, every file has an associated inode. This datastructure contains the following information:

- The file’s metadata

- 12 Indirect pointers, where each pointer ‘points to’ a data block of the file, in order

- 1 Indirect pointer, which points to the head of another list of 12 indirect pointers, should the first 12 not be enough to cover the size of the file

- 2 Indirect pointers, the same logic as above, but containing 2

- 3 Indirect pointers, again but containing 3

Below is an example using file.txt’s inode:

inode structure

---------------

inode file.txt

| metadata |

| 12 ind. | ptr(0) --> | datablock |

| | ...

| ptrs | ptr(11) --> | datablock |

| ind. ptr | --> | 12 ind. | ptr(0) --> | datablock |

| | ...

| ptrs | ptr(11) --> | datablock |

| 2 x ind. | --> | ind. ptr | --> | 12 ind. | ptr(0) --> | datablock |

| | ...

| ptrs | ptr(11) --> | datablock |

| ptrs | --> | ind. ptr | --> | 12 ind. | ptr(0) --> | datablock |

| | ...

| ptrs | ptr(11) --> | datablock |

|3 x ind. ptr| ...

Following the Unix philosophy that ’everything is a file’, directories also have inodes, but instead of mapping the first ind. ptr to a file’s datablock, they map a filename to its inode:

inode structure

---------------

directory inode

| metadata |

| 12 ind. | ptr(0) --> | file1.txt's inode |

| | ...

| ptrs | ptr(11) --> | file12.txt's inode |

| ind. ptr | --> | 12 ind. | ptr(0) --> | file13.txt's inode |

| | ...

| ptrs | ptr(11) --> | file24.txt's inode |

| 2 x ind. | ...

| ptrs | ...

|3 x ind. ptr| ...

So to get the data of a file ‘/foo/file.txt’ from ‘/’:

"/" "/foo" "/foo/file.txt"

| "/"s inode |

...

| ind. ptr | --> | "foo"s inode |

... ...

| ind. ptr | --> | "file.txt"s inode |

... ...

| ind. ptr | --> | data block |

...

The main differences then, between low and high-level:

- Low-level methods all take a fuse request as an argument, high-level methods do not

- Lookup and forget methods are used by the high-level when the kernel removes an inode from either the inode or dentry cache. Due to the high-level not using inodes, the low-level handles this instead

When a request comes in from the kernel, the low-level lib takes it and either searches in the low_level_ops struct or the high_level_ops struct depending on which api the developer used and runs the code found inside. The high-level will pass the response down to the low-level which will handle it there before passing the response to the kernel, hence one of the main reasons of the performance difference of the two apis.

Per connection session information

The user-kernel protocol (mentioned previously) offers a mechanism to store opened file’s/dir’s information. In the low-level lib, each method gets a fuse_file_info struct which is used to hold such information. It contains a filehandle which can point to the file/dir. Taking advantage of this capability allows the protocol to be stateful. Developers are also allowed to leave it stateless (by not using the struct), but this leads to the daemon constantly needing to open/close the files and directories manually upon each operation, leading to potential performance degredation.

Queues

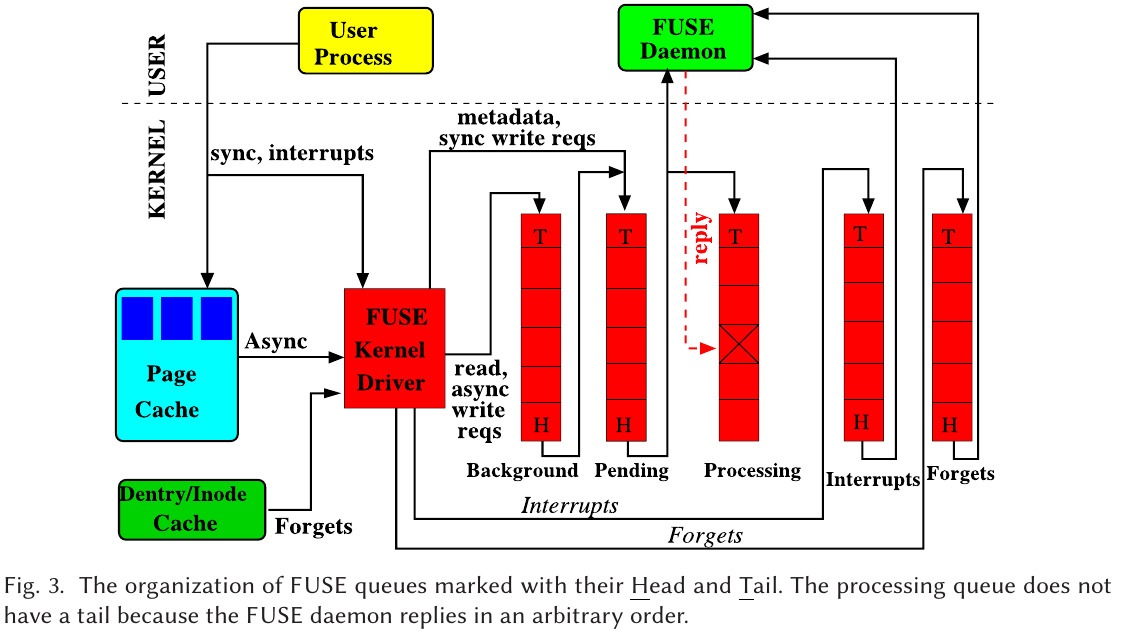

The fuse kernel holds 5 different queues, with each queue providing a specific purpose:

- Interrupts (highest priority) - For all interrupt requests

- Forgets - For all forget requests

- Pending - Latency sensitive requests (related to metadata)

- Background - All other requests (read/write etc)

- Processing - The requests that are currently being processed by the daemon

It is important to note that one request can only belong to one queue at a time. For performance reasons forget requests must be throttled as many can come at once and take over the queue, hence why there is a seperate forget queue. For every 8 non-forget request there are 16 forgets. The oldest requests in the pending queue are ’taken’ by the user space daemon, and when this happens the kernel updates the queues to match, by removing the request from the pending queue into the processing queue. When the user-space daemon replies to the kernel that a process is finished (via the /dev/fuse character device), the kernel removes this request from the processing queue. This queue doesn’t have a tail due to the daemon replying with confirmation of arbitrary requests, thus there is no order there. Another important note is that interupt and forget requests do not get a reply, thus those requests are removed completely when taken.

Splicing and FUSE buffers

Every read/write call to /dev/fuse requires a memory copy of the data between the kernel and user-space. Write requests and read replies can be the most harmful due to the potential size of the data that needs to be processed. FUSE uses splicing (offered by the linux kernel) which allows the user-space to transfer data between 2 in-kernel memory buffers without the need to copy the data to user space.

In the low-level api, the write_buf method can be used to splice data from /dev/fuse into a linux pipe. It then passes the data as a buffer containing the pipes fd. For this to happen there must be more than a single page of data. It is important to note that for reads in the low-level api, developers must differentiate between splice and non-splice flows inside the read method itself.

References

- [1] : Vangoor, Bharath Kumar Reddy, Vasily Tarasov, and Erez Zadok. “To {FUSE} or Not to {FUSE}: Performance of User-Space File Systems.” In 15th {USENIX} Conference on File and Storage Technologies ({FAST} 17), pp. 59-72. 2017.

- [2] : Tanenbaum, A. S., and H. Bos. “Modern Operation Systems 4th Edition.” (2014).

- [3] : Inode structure, Udacity, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMVj22EWg6A